The science police and the flaky dilettantes: food gets scientists going

December 6, 2012 at 1:51 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | 4 CommentsTags: Bad Science, Ben Goldacre, Ed Yong, nutrition, personality

I recently read the following tweet, from influential science blogger Ed Yong:

If you want to look at a field that is basically noise, with virtually no signal, check out nutritional epidemiology ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23193004

— Ed Yong(@edyong209) November 30, 2012

Continue Reading The science police and the flaky dilettantes: food gets scientists going…

Science and the media: is impact especially bad for brain science?

November 29, 2012 at 2:32 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | 4 CommentsTags: Information processing, Neuron, neuroscience, philosophy of mind, representation

I’m a science writer. I signed up long ago to the principles of open science, and I do my best to let people know about the magnificent achievements of modern neuroscience. Insofar as introverts can be evangelical, I’m spreading the good news about brain research. To do this, I and many others like me need publicity. We need the media.

I’m a science writer. I signed up long ago to the principles of open science, and I do my best to let people know about the magnificent achievements of modern neuroscience. Insofar as introverts can be evangelical, I’m spreading the good news about brain research. To do this, I and many others like me need publicity. We need the media.

And yet, I have a deep and growing fear that the current excited courtship between research, especially brain research, and the media may not necessarily be the good thing people seem to think it is.

This is not just the usual anxiety about requirements for ‘impact’ in funding applications, and the distorting effects of rewarding instantly popular research (see for instance this report from NHS Behind the Headlines). It’s more fundamental, and it’s particularly relevant to the sciences of the mind and brain.

It’s also quite tricky to articulate, so please, bear with me. Here goes. Continue Reading Science and the media: is impact especially bad for brain science?…

Wearily kissing the rod: UK academics and the REF

November 15, 2012 at 6:08 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | 1 CommentTags: Academia, higher education, REF, Research Assessment Exercise, Research Excellence Framework, university

(a long post, this one, about who gets research money)

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the UK government’s way of assigning money for academic research.

It’ll happen in 2014. Work to prepare for it has been ongoing since its predecessor, the Research Assessment Exercise, finished, if not before.

As Jenny Rohn has recently commented in the Guardian,and many others have also said, the REF is a real problem for UK science, and for academia in general. To solve that problem, we need to understand why the REF is happening.

The core issue, as the government sees it, is that limited resources and the pressure to provide value for money (right now) create a demand that money should only be spent on good research. Unfortunately, it can take decades to work out which research is good.

There’s also considerable debate about what good research is. Academics tend to think of good research as being scholarly: rigorous in its methods, intellectually coherent and persuasive, novel and insightful (it adds new knowledge), enriching (it adds new understanding, e.g. by relating previously unrelated phenomena), and fruitful (it generates lots of new ideas). Governments and funders seem to think of good research as being efficient at generating lots of future research jobs, cash for the economy, or positive publicity for UK PLC. But scholarship can cost money and take time without producing immediate economic rewards, so it appears inefficient over the short term of a government (5 years) or a REF assessment cycle (4 years).

What to do? Well, you could try short-circuiting the judgement of posterity by asking current academics what they think of other people’s research. Brilliant! That ticks all the boxes of consultation, transparency, stakeholder participation, and so on.

Unfortunately, it also has its problems. For one, there is as yet no firm evidence that having an assessment system like the REF improves research quality. Senior academics like Stefan Collini have argued that it will make things worse, not better. But for all that, it’s going ahead with surprisingly little protest from academia.

Why? Here are some reasons that may be relevant.

1) It’s conservative. The REF emasculates one major source of resistance, the ideal of academic independence, because the government can turn round to academics and say, ‘Hey, you’re the people making the judgements, all we’re doing is divvying up the funding at the end’. Actually, it’s not so much the academics as the university managers who make the judgements, because they set the criteria for who’s ‘REFable’ among their staff. This intensifies conservative tendencies, because fashionable topics are rewarded more; yet academia needs more new ideas, not fewer. Because universities do much of the rating in advance, by choosing whose work to submit to the REF, that conservatism sets in early. Because it is more senior staff who do much of the rating, that adds to the risk that new ideas will be squeezed out.

Making institutions choose whom they submit is the biggest flaw in the system, in my view. Academics need to be judged by their peers — other academics who are expert in their field. Asking a psychologist to rate the work of a neuroscientist in the same university department might make sense if the psychologist works on something brain-related, but if they don’t? If the psychologist’s field is the closest in that department to what the neuroscientist is doing, chances are they’ll get to decide their REFability, whether or not they speak the same language, think about science in the same way, or understand the research. Let’s hope the psychologist isn’t an undeclared cat lover who rates the neuroscientist down because they’re doing animal research. At least in a grant application you’ve some chance that assessors will be experts in your field!

2) It’s bad for diversity. The REF structure allows government to externalise much of the cost. Only those submitted as REFable will then have their work assessed by an expert panel. The considerable downside is discrimination against minority topics, which are less likely to be assessed by expert colleagues in the same institution, since there may not be any. Good scholarship should be rewarded whatever the topic, but in practice that doesn’t happen. Instead, people look at a piece of work, think, ‘this is a marginal subject’, or ‘I don’t like this person’s attitude’, and downgrade it in REF terms, whatever its intellectual quality. Meanwhile, there’s plenty of fashionable nonsense earning plaudits, even though it is less rigorous, less intellectually coherent, perhaps less fruitful (and often not even as well-written). Academics aren’t immune to the human herd instinct, and the REF gives it free rein. Work published in top-ranking journals and by top-ranking international publishers can thus be ranked so low by colleagues that it may never get as far as a REF expert panel. The solution is to have all academics submitted, not just those selected by the institution.

3) It’s unclear. The lack of clarity in the REF has been a gift to those running it and a source of considerable stress to those being processed. Many academics, particularly those at junior and middle levels, are now so demoralised that they dare not speak out. There are rumours that those not ‘returned’ (submitted to the REF) will be taken off research onto teaching-only contracts if they are not REF-returned. There is a strong feeling that any adverse comment could mark you as a troublemaker in the eyes of those with power to ruin your career. University managers and government ministers could state, for the record, that they have no such plans, and that academics are allowed, and expected, to criticise how their universities are run. That is not the message that is currently reaching staff. They don’t know what to think, because the criteria are so vague; and uncertainty breeds fear — which the leadership has largely left to fester. Of course it has. Demoralised academics are far less trouble.

4) It’s burdensome. Staff can also be demoralised by adding to their workload, and the REF has done this too. Those called to assess submissions (which may be papers, or books, four pieces per person) must do the work alongside their ordinary jobs. Universities are even hiring people to help them with their REF submissions. They’re also wasting loads of staff time on REF bureaucracy, further stressing already overworked academics — who fill in the damn forms in what should be their research time, and then risk being punished for not doing enough research!

5) It’s bad for morale. Staff can be demoralised even more by increasing the emphasis on competition. Academia is in part competitive, but the traditional model was inter-institutional competition (think the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race!). Institutions which looked after their own fostered a collegiate culture which allowed for the development of a ‘critical mass’ of intellectual cooperation. Academics who felt secure enough to share their early ideas with others were able to benefit from their comments, to cross-fertilize ideas, to generate new hypotheses and new collaborations. If every person is out for his or her own career, and forced to compete with the people he also has to work with, that causes intense psychological discomfort. It also reduces creativity. Years after science discovered that competition isn’t what life’s all about after all, university management is still stuck in the 1980s. The REF encourages game-playing. Universities are now hiring science writers to help craft their impact case studies. That money could be going on better teaching provision.

6) It’s short-sighted. Finally, there’s the obvious point that excellence doesn’t spring from a void. Like a sought-after orchid, it needs an entire ecosystem to flourish. Keep picking the flowers, moreover, and the number of orchids will drop. The REF’s focus on excellence, so appealing in principle, is not so clever in practice, because it risks creating an academic wasteland. Healthy ecosystems, of course, have weeds and other apparently useless plants. Weeding out useless academics is a popular goal, but using the REF to do this is like weeding a garden with a JCB. Weeding by hand, however, would demand a lot of time, skill and effort from university management.

In all of this, the REF reminds me, in a mild way, of the techniques of ‘thought reform’ used by the Chinese Maoists to subjugate political dissenters. They set people against each other, constantly reviewing and criticising them, and forcing them to criticise each other. Hard, mind-numbingly tedious work also helped wear the dissidents down, as did the fear and uncertainty in which they were kept. The thought reformers knew that unspecified threats of punishment can be more effective than actually listing consequences, and they were careful to leave their criteria for good and bad behaviour vague and flexible. Interminable discussions of ideology were coupled with frustrating lack of clarity on the details; one might therefore sin without understanding how. This gave the impression that judgement of who was ideologically correct was essentially arbitrary.

The result was obedience, with or without commitment. People could be brought to kiss the rod that beat them, to praise the ideals that oppressed them, or at least to keep sullenly, fearfully quiet.

Of course, analogy is not identity. Thought reform was conducted in prison camps, and used torture. Academics are free to leave universities, if they don’t mind going on the dole (jobs are scarce, and speaking out against university management is unlikely to make them less scarce). As for hiking workloads, imposing arbitrary bureaucratic burdens which shrink research time, taking away the sense of having any control over teaching or admin, and making staff feel that they are at the bottom of the status heap, these techniques may do psychological harm, but they’re not torture.

But nor are they a sensible way to run higher education. The gains in efficiency are short-term, and largely illusory. They seem desirable because the government’s research funds are not handed out by the same people who are paying even for the teaching budget, let alone for the sick leave of overstretched academics. Nor are today’s votes significantly affected by future reductions in academic creativity.

The REF is pernicious and deeply flawed. Many people have pointed out the problems — yet it’s going ahead. When that happens, it’s time to start asking cui bono? Is the continued existence of the REF just down to inertia in the system, or might those flaws be there for good political reasons?

So who does stand to benefit from the REF? Academics? The most senior ones, perhaps, in the most highly-regarded subjects. But not the rest.

The advantages for government and management, however, are obvious. They can claim to be pursuing efficiency and excellence and put the blame for any future failures in research on universities. They also lessen the chances of a revolt among academic staff by the time-tried tactics of divide-and-rule, distraction, and exhaustion. And they save money by making those same academics do most of the work.

Seen from this angle, the REF starts to look like rather a good thing. Could that be why we still have it?

Related articles

- Must all postgrad research have ‘impact’? (guardian.co.uk)

- Dodgy dealings in UK higher education | Jenny Rohn (guardian.co.uk)

- How to defend universities | Paul Seabright (Times Literary Supplement)

The Royal Society: promoting women in science (more data)

November 13, 2012 at 1:15 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentTags: Nobel Prize, Royal Society, Wikipedia, Women in science

Today I’m off to hear Sir Paul Nurse, President of the Royal Society, give the Erasmus Darwin Memorial Lecture. It should be fascinating.

However, as I probably won’t get to ask about women in science, and the Society’s campaign to promote women scientists (see also Wired on the topic), I’ve decided to post some relevant data here.

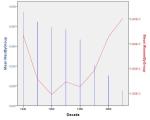

Below are three graphs

The first graph (left) shows the number of men (blue) and women (red) elected every year from when women were first allowed to join. As you see, the numbers of male Fellows grew rapidly after the Second World War, and then steadied. The number of female Fellows, after some early years’ tokenism, began to grow only much later, in the 1990s.

HOWEVER

These raw numbers don’t take into account the fact that the Royal Society nearly tripled in size between 1945 and 2010. This isn’t just because of more people being elected, it’s also because they have been living longer, as membership is granted for life.

So, the middle graph shows the numbers of men and women as a proportion of the overall number of Fellows in the Society, grouped by decade to show a clearer picture. It confirms that the proportion of men has been dropping most noticeably since the 1990s, as more women have been elected. After an initial surge, not much happened for the ladies during the 60s, 70s and 80s. Since then, though, things have been improving.

HOWEVER

To show the trends clearly, the middle graph has two different scales on its vertical axes. This allows easy comparison of how gender proportions are changing, but it hides the real magnitude of the gender difference. So the third graph (right) plots the proportions on identical scales. Yes, that red line crawling wearily along the bottom is for females.

TO CONCLUDE …

Between 1945 and 2010, 2512 men (about 95%) and 129 women (about 5%) have been elected.

Between 2010 and 2010, though, 451 men (about 90%) and 50 women (about 10%) have been elected.

So if you’re keen on working towards a less unequal gender balance at the top levels of science, this particular leading organisation appears to be heading in the right direction. But there’s still a VERY long way to go.

You’re breaking up … anaesthesia and the brain

November 6, 2012 at 5:25 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentTags: anaesthesia, Brain, consciousness, neuroscience, Oscillation, Slow-wave sleep, Unconsciousness

Lewis, L. D., V. S. Weiner, et al. (2012). “Rapid fragmentation of neuronal networks at the onset of propofol-induced unconsciousness.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A fascinating paper in the journal PNAS, this. OK, it’s in patients (pretty much has to be, given they’re using intracranial electrodes), and only three of them, but it offers tantalising ground for speculation, which is always fun. And it shows how influential the notion of brain oscillations is becoming. ‘Tweren’t always thus.

Behaviour: epilepsy patients were tested during loss of consciousness by being given the anaesthetic propofol and asked to press a button when they heard a (frequent) tone. Two consecutive non-responses were taken to mean that the anaesthetic had successfully knocked them out. Propofol boosts GABAergic activity.

Brain recordings: these were taken of the intracranial electrocorticogram (i.e. global electrical activity, if one can call the brain a globe), single neurons, and the intermediate level of the local field potential (LFP), all in the same region, temporal cortex. Nice.

Findings: what the authors found, in their own words, was ‘a functional isolation of cortical regions while significant connectivity is preserved within local networks’, slow oscillations in the local field potential, and ‘short periods of normal spike dynamics still can occur during unconsciousness’. Initially neuronal spiking is suppressed, but though cells’ activity may recover to pre-anaesthetic levels, the patterns are different — short bursts, interspersed with silence, the activity coupled to the slow oscillations. And the patient remains unconscious.

Conclusions: so to put it crudely, consciousness doesn’t seem to depend on the number of spikes, so much as on the long-range connections between active areas. The local slow oscillations, which look a bit like the slow waves of slow-wave sleep (but more fragmented and with faster onset), appear to have different phases in different areas, suggesting that coupling between areas is interrupted. Apologies if this is starting to sound like a bad neuro take-off of Fifty Shades of Grey, but in consciousness, it seems, coupling’s what it’s all about.

Having said which, as the authors point out, they don’t yet know ‘whether the slow oscillation is sufficient to produce unconsciousness’. And this kind of functional breaking up may not be the only way in which we humans can be rendered temporarily insensate. MRN, of course (more research needed).

Still, it’s interesting to think about implications: for attempts to create artificial conscious entities, for what may be going on in Alzheimer’s, and for the science of dreams, to name but three. All those patients’ reports of strange sensations and half-remembered awareness while supposedly unconscious seem less neurotic now. Fascinating stuff!

What is the brain supremacy?

November 5, 2012 at 6:57 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | 3 CommentsTags: Brain, neuroscience, Research

The brain supremacy is a great, rapidly- developing change in science, in which the traditional dominance of the physical sciences will be challenged, and then usurped, by the growth of the biological, and especially the brain sciences.

developing change in science, in which the traditional dominance of the physical sciences will be challenged, and then usurped, by the growth of the biological, and especially the brain sciences.

When that happens, our culture, including the culture of science, will have to change, because both are built on outdated assumptions. As a bonus, the change could take scientific hubris down a peg or two, as we realise just how much harder brains are to study than anything we’ve tackled so far. That’s no harm either! Humility’s an unfashionable virtue in this self-promoting age, and it’s a lot harder to slip from confidence to arrogance when you’re trying to analyse a living brain.

Three great flows in the river of science are converging. Expect a white-water ride, as the power of physics-derived brain research methods and the force of the genetics revolution meet the youthful energy of a science emerging from childhood into a fully-fledged research field. When I started out, neuroscience was a branch of physiology. No longer.

The brain supremacy can’t come soon enough for me, for three reasons. Firstly, because time’s getting on in this particular life-path! Secondly, because it’s going to be amazing to watch. Neurotech is already phenomenal; as the brain supremacy takes shape its power will reach awe-inspiring capacities. How about dream recording, selective memory erasure, mindreading? How about the facility to share dreams, or download artificial experiences? How about the ability to reprogramme your beliefs and desires? It’s going to be a fascinating journey, seeing even a few of these promises come to pass.

Finally, thirdly, there’s my great hope: that the brain supremacy could make us all more human. Minds need more careful handling than rocks or proteins; the ethical constraints are tighter. The potential for misuse of the new technologies — which is admittedly nightmarish — will, I hope, make us more careful of each other. Every human brain is gloriously unique. The more we recognise that, the harder it may become to commit the atrocities which ruin and destroy them …

… and the easier it will get to work towards cures for hurt neurons. Think what we could do if we gained the gift of precision brain control. Might fanaticism, violence and psychopathy become curable disorders? Might the hideous damage inflicted by childhood abuse, or the diseases of old age, be reversible at last? Those are goals worth chasing.

I’m so lucky to be alive to see this time when, more than ever before, we hold the hope of a better future in our hands.

The Royal Society: promoting women in science

October 19, 2012 at 2:05 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentTags: Nobel Prize, Royal Society, Wikipedia, Women in science

Today the Royal Society is doing a Wikipedia edit-a-thon about women in science, as part of its campaign to promote women scientists (see also Wired on the topic).

Below is a graph indicating why they need promoting, especially at the highest levels. The image shows the sex ratio of Royal Society Fellows by year, since women were first allowed to join in 1945 — only a few decades after they gained the vote, and access to universities.

Note how, after an initial splurge, the rate of women joining flattened out until very recently. Note also that the number of Fellows has risen considerably since the Second World War, and most of the new additions have therefore been men.

Note also that, as of 2010, the sex ratio is still under 6%. If there were equal numbers of men and women, it would be at 50%.

At current growth rates, we can calculate that those looking for gender parity at the highest level of UK science will have to wait until the late 2080s.

The Royal Society can console itself, however: at least it’s doing better than the Nobel Prizes. Comparable figures? As of 2010:

Physiology/medicine: 5.1 %

Chemistry: 2.5%

Physics: 1.1%

How about a big-value science prize or prizes for women only? To be christened the Nobelles, of course! That might change the gender bias of science faster than any amount of Wikipedia editing.

Twitterbrain: a challenge for brain people everywhere

October 18, 2012 at 3:59 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentTags: Anterior cingulate cortex, Prefrontal cortex, Twitter, twitterbrain

Can you help me out?

The challenge: sum up a brain area’s function in a tweet (or equivalent 140 characters, if you’re not on Twitter).

The more I read about the brain, the less I feel I know. What on earth does the posterior cingulate actually do? Come to that, what about the anterior cingulate? Error detection, anxiety regulation, willpower, I’ve seen all sorts of attributions. But can these masses of data be clarified down to a single tweet? Or is this an impossible challenge?

Below is how far I’ve got (regularly updated. I’ve started so I’ll damn well … if not finish, at least proceed!)

*******************

Primary visual cortex processes inputs from the eyes, assessing them in terms of basic features like orientation.

The amygdala adds emotional salience to sensory inputs. It is particularly associated with fear responses to threats.

The hippocampus is involved in storing information in long-term memory, and also in spatial navigation.

The posterior parietal cortex processes data about spatial locations and generates representations of the body’s position.

The striatum is a major component of the brain’s dopamine system, linked to incentives, motivation, and reward signalling.

Primary auditory cortex processes inputs from the ears, assessing them in terms of basic features like pitch.

The locus ceruleus controls noradrenaline input to cortex, regulating its flexibility and responsiveness. See for a review.

Primary somatosensory cortex processes inputs from the skin and muscles, contributing to feelings of touch and body position.

The pituitary gland releases hormones involved in reproduction, homeostasis (e.g. blood pressure and water balance), & growth.

The fusiform gyrus participates in face recognition.

The frontal eye fields are involved in the generation of voluntary eye movements, notably the quick jumps called ‘saccades’.

The primary motor cortex generates ‘command signals’ controlling movements.

The orbitofrontal cortex is involved in calculating what values should be assigned to objects in the environment.

The amazing astrocyte

October 10, 2012 at 12:02 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentTime was when neuroscience students learned about brain cells — meaning neurons. Other kinds of brain cells were recognized, but it was thought they played merely support roles. As a result, explanations of brain function were like explanations of society which only refer to men: incomplete and misleading. Not any more. Read on

Are Republicans bad for you?

October 4, 2012 at 10:24 am | Posted in Uncategorized | 2 CommentsTags: Democrats, GOP, homicide, James Gilligan, Republican, suicide, unemployment

I can’t help wondering whether Dr James Gilligan feels himself to be in that special circle of hell reserved for academics — the one where, however clear and well-expressed your message, however startling and well-presented your data, no one actually listens. His book Why Some Politicians Are More Dangerous Than Others is a shocker, not least because it includes a call for the abolition of the US Republican Party (it seems he thinks it’s past repair). And I exaggerate in saying no one listened; it was multiply- and well-reviewed. Yet here we are, a year after publication … and damnit, the so-and-sos might even win the election. Continue Reading Are Republicans bad for you?…

Create a free website or blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and comments feeds.

You must be logged in to post a comment.